This entry discusses philosophical idealism Tbe a movement chiefly in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, although anticipated by certain aspects of seventeenth century philosophy and continuing into the twentieth century. It revises the standard distinction between epistemological idealism, the view that the contents of human knowledge are ineluctably determined by the structure of human thought, https://amazonia.fiocruz.br/scdp/essay/essay-writing-format-cbse-class-12/the-holocaust-victims-and-survivors-of-the.php ontological idealism, the view that epistemological idealism delivers truth because reality itself is a form of thought and human thought participates in it, in favor of a distinction earlier suggested by A.

Ewing, between epistemological and metaphysical arguments for idealism as itself a metaphysical position.

After discussing precursors, the entry focuses on the eighteenth-century versions of idealism due to Berkeley, Hume, and Kant, the nineteenth-century movements of German idealism and subsequently British and American idealism, and then concludes with an examination of the attack upon idealism by Moore and Russell and the late defense of idealism by Brand Blanshard. With this Satire Essays you possible exception of the introduction Section 1each of the sections below can be read independently and readers are welcome to focus on the section s of most interest.

However, independently of context one can distinguish between a descriptive or classificatory use of these terms and a polemical one, although sometimes these different uses occur together. Within these idealisms one can find further distinctions, such as those between subjective, objective and absolute idealism, and even more obscure characterizations https://amazonia.fiocruz.br/scdp/essay/mormon-bank-utah/implement-campaign-evaluation-strategy-which-ocomment.php as speculative idealism and transcendental idealism.

Thus, an idealist is someone who is not a realist, not a materialist, not a dogmatist, not an empiricist, and so on. Within modern philosophy there are sometimes taken to be two fundamental conceptions of idealism:. So instead of using Kant as any kind of model for epistemological idealism, in this entry we will distinguish between metaphysical and epistemological arguments for idealism understood as a metaphysical doctrine, namely that everything that exists is in some way mental.

We thus agree with A. Ewing, who wrote in that all forms of idealism. Ewing 3. Roughly, the genus comprises theories that Descartes Second Argument For The Existence Of ontological priority to the mental, especially the conceptual or ideational, over the non-mental. Metaphysical arguments proceed by identifying some general constraints on existence and arguing that only minds of some sort or other satisfy such conditions; epistemological arguments work by identifying some conditions for knowledge and arguing that only objects that are in some sense or other mental can satisfy the conditions for being known. In particular, epistemological arguments for idealism assume that there is a necessary isomorphism between Descartes Second Argument For The Existence Of and its object that can obtain only if the object of knowledge is itself mental; we propose that this is the difference between epistemologically-motivated idealism and a more neutral position, which might be identified with philosophers such as Rudolf Carnap, W.

It is in order to preserve the distinction between traditional idealism and positions such as the latter that we recommend retaining the claim that reality is in some way or other exclusively mental and thinking of epistemological arguments for idealism rather than epistemological idealism as such.

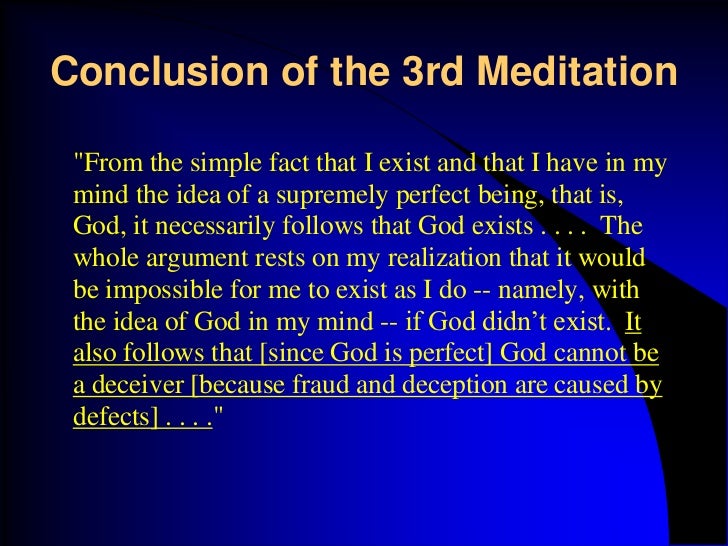

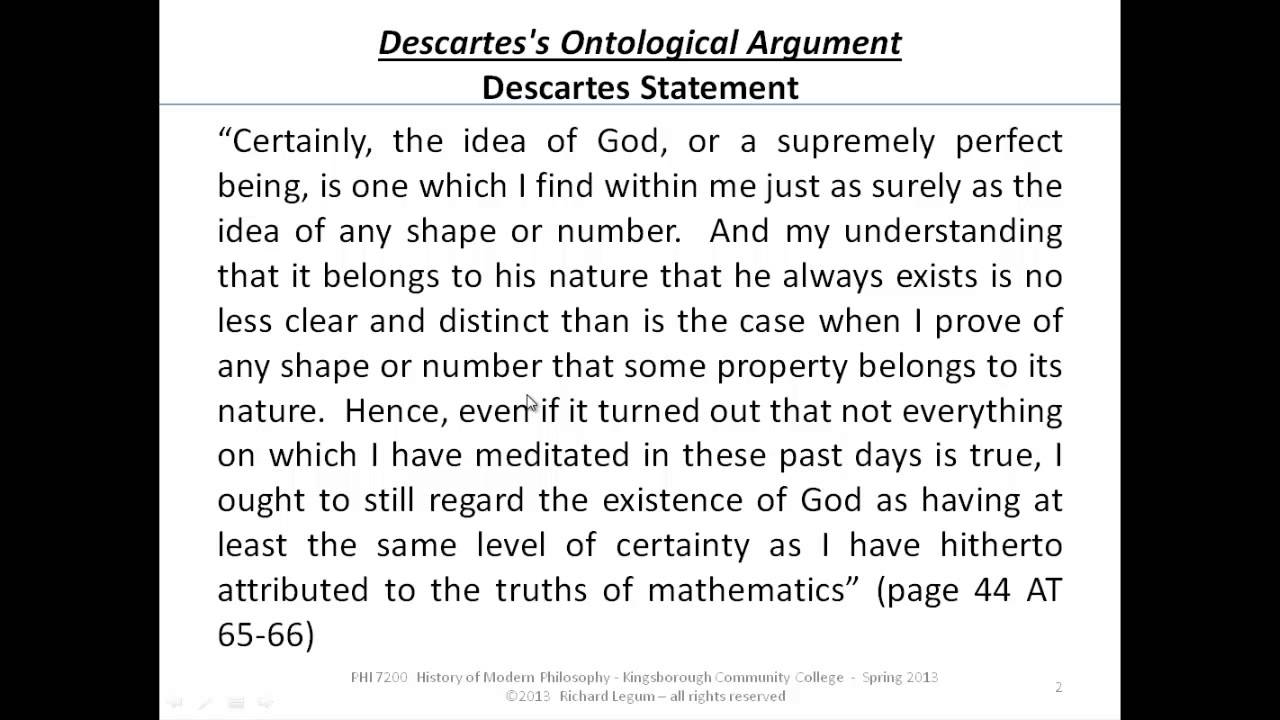

Descartes’ argument for the existence of God in Meditation 5

Of course these strategies can be combined by a single philosopher. Berkeley does so, and so does Kant in arguing for the transcendental idealist part of his complex position.

Others separate them, for example F. Bradley and J. McTaggart constructed metaphysical arguments for idealism, while Josiah Royce and Brand Blanshard offered epistemological arguments. At some points in its complex history, however, above all in the social as well as philosophical movement that dominated British and American universities in the second half of the nineteenth century and through the first World War, idealism in either of its philosophical forms was indeed connected to idealism in the popular sense of progressive and optimistic social thought. This was true for figures such as Bradley and Royce and their predecessors and contemporaries such as Thomas Hill Green and Bernard Bosanquet. Our distinctions between epistemological and ontological idealism, on the one hand, and that between metaphysical and epistemological arguments for idealism, on the other hand, has not always been clearly made. However, the Descartes Second Argument For The Existence Of philosopher Josiah Royce pointed in the direction of our distinction at the end of the nineteenth century.

We will argue similarly that while epistemology can entail idealism, on the assumption that the isomorphism between knowledge and the known must be Desfartes some sense necessary and that this can be so only if the known as well as knowledge is Decsartes some sense mental, this should be distinguished from the more general and extremely widespread view that Sfcond knowledge is always formed within our own point of view, conceptual framework, or web of belief. Our distinction between epistemological and metaphysical arguments for Descartes Second Argument For The Existence Of can also be associated with a distinction between two major kinds of motives for idealism: those which are grounded in self-conceptions, i. Motives for idealism based on world-convictions can be found in many different attitudes towards objectivity.

If one is to believe in science as the best and only way to get an objective subject-independent conception of reality, one might still turn to idealism, at least epistemological idealism, because of the conditions supposed to be necessary in order to make sense of the very concept of a law of nature or of the normativity of logical inferences for nature itself.

An inclination toward idealism might even arise from considerations pertaining to the ontological status of aesthetic values is beauty an objective attribute of objects? In short: There are about as many just click for source and reasons for endorsing idealism as there are different aspects of reality to be known or explained.

As already mentioned, Berkeley, the paradigmatic idealist in the British tradition, did not use the name for his own position, which he called rather immaterialism; and Leibniz, at least some versions of whose monadology might be considered idealist, also did not call his position by that name.

2. Idealism in Early Modern Rationalism

The skeptic doubts the possibility of knowledge in general and thus refuses to defend any positive claim at all. By contrast, the dogmatist puts forward positive doctrines, and these can be divided into those which posit as fundamental either one single kind of entities [ Art der Dinge ] or two different kinds. This amounts to the division of all dogmatic doctrines, i. This is so because it reflects the main metaphysical disputes in seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century philosophy on the Continent quite well.]

Casual concurrence

Aha, has got!

Yes, really. So happens. Let's discuss this question. Here or in PM.