![[BKEYWORD-0-3] Income Inequality Among Developing Countries](https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Martin_Ravallion/publication/262608920/figure/fig2/AS:496481088278529@1495381723269/Evolution-of-average-inequality-within-countries_Q320.jpg) Income Inequality Among Developing Countries.

Income Inequality Among Developing Countries.

This entry presents the empirical evidence of how inequality between incomes has changed over time, and how the level of inequality varies between different countries. We also present some of the research on the factors driving the inequality of incomes.

A related entry on Our World in Data presents the evidence on global economic inequality. That entry looks at economic Study The Angel Income Inequality Among Developing Countries how global inequality has changed and is predicted to continue changing in the future.

The idea behind this curve is that in a very poor society inequality cannot be very high: Imagine if the average level of income were just the bare minimum to survive, in such an economy there could not possibly be any inequality as this would necessarily mean that some people have to be below the minimum income level on which they could survive. When average income is a little higher it is possible to have some small level of inequality, and the IPF shows how the maximum possible inequality increases with higher average income.

This means that in these societies, inequality was as high as it possibly could have been. In the cases of Holland and England, we see that during their early development Income Inequality Among Developing Countries moved away from the IPF and the level of inequality was no longer at the maximum. The United Kingdom is the country for which we have the best information on the distribution of income over the very long run.

This information is visualized in this chart.

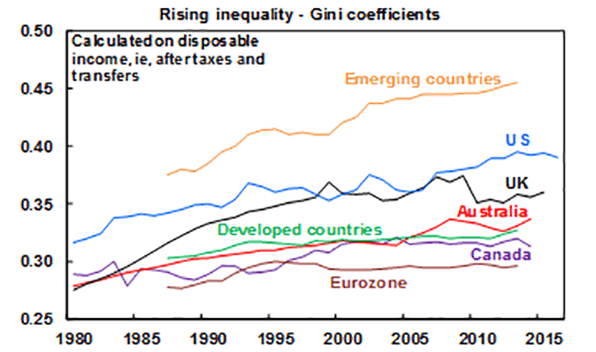

The estimates presented in this visualization suggest that inequality in the UK was very high in the past, and did not change much until the onset of industrialization. Starting in the late 19th century, income inequality began to decrease dramatically and reached historical lows in the late Income Inequality Among Developing Countries.

From the early s onwards, we see that the UK experiences a divergence between what the Gini and the top income shares tell us about inequality. The Gini Ineuality flat over these two decades and, if anything, fell somewhat during this period.

This tells us that inequality across the bulk of the distribution has not increased further in the UK. At the very top, however, the evidence shows a different story. Top income inequality is measured as the share of total income that goes to the income earners at the very top of the distribution. Historical top income inequality estimates are reconstructed from income tax records, and for many countries these estimates give us insights into the evolution of inequality Countrise more than years.

Navigation menu

This is much longer than other estimates of income inequality allow as is the case with estimates that rely on income survey data. The fact that income shares are measured through tax records implies that these estimates measure inequality before redistribution through taxes and transfers. What we can learn from this long-term perspective is summarized in this visualization. After the s inequality in the USA started increasing, and eventually returned to the level of the pre-war period. We see that this U-shaped long-term trend of top Income Inequality Among Developing Countries shares is not unique to the USA. In fact the development in other English-speaking countries, also shown in the left panel, follows the same pattern.

However, it would be wrong to think that increasing top income inequality is a universal phenomenon. The income share of the rich has decreased over many decades, and just like in the English-speaking countries, it reached a low point in the s. Income inequality in Europe and Japan is much lower today than it was at the beginning of the 20th century. A lesson that that we can take away from this empirical research is that political forces at work on the national level are likely important for how incomes are distributed. A universal trend of see more inequality would be in line with the notion that Income Inequality Among Developing Countries is determined by global market forces and technological progress. The reality of different inequality trends within countries suggests that the institutional and political frameworks in different countries also play a role in shaping inequality of incomes.

This means that rising inequality is most likely not inevitable. It is important to Countrie that the top income measures of inequality that we discuss above refer to inequality in the distribution of market incomes. And market incomes are not the same as disposable incomes, because most people pay taxes and receive transfers from the government.]

It agree, very good message